There’s been a lot of talk recently on self-sovereign identity (SSI), as it appears to be the next “new thing” in the digital identity sphere, especially in the context of possibly replacing the traditional public key infrastructure (PKI) based offerings.

Here, I aim to pull apart the kinds of identities we use every day; those in government-led society and those online, and find where self-sovereign identity might fit and where it’s not appropriate. I also want to discuss two aspects of SSI that often get bundled together and cloud the conversation - identity and data exchange. Since SSI relies on data exchange to simply identify ourselves, these two offerings get talked about as one, leading to misconceptions and limited opportunities. I’ll start with identity and uncover what’s important, where. In the second post, I’ll dive into data exchange, highlighting what needs to be considered to achieve a balance of transparency and trust, privacy, control, and security.

Does Self-Sovereign Identity Fit for e-Government Services?

Over the past few years, the discussion around SSI has focused on trying to solve problems that I, and seemingly the SSI community themselves, have struggled to identify. I’ve actually written on this topic before, sharing my concerns on SSI and its feasibility in society as it is today. The more I see governments considering it, the more I feel the need to understand what is the problem being solved.

I don’t really question the principles behind SSI, like privacy and data control in the hands of the end-users, they’re sound, and do align closely with the way society is moving. The problem is, I see SSI being pitched as the replacement for log-in with Facebook or Google with reference to government services or use with social security numbers. Social networks and online government services do not mix. Governments might use social media to share information, but they certainly don’t allow their citizens to apply for a new passport with Facebook credentials. If SSI is here to create a more trusted, less tracked way of using online services like Netflix, Amazon, and Spotify, I’m all for it, but we must not confuse government-issued identities with unverified characters born on the internet.

Principles for Digital Identity

There are a few different lists of principles guiding SSI, with the majority of the key ideas agreed upon across the community. Privacy, verifiability, transparency, decentralisation, and interoperability are a few of the main focuses, alongside security and inclusion. Many of these points remind me of a general election campaign in Australia in the 1950s, where one of the candidates claimed he would not be taxing sheep if he was elected. This, in turn, forced his opponent to start defending himself about something that he never planned on doing. Similarly, we now find traditional PKI-based digital identity defending itself on topics of end-user control and privacy.

No digital identity service can be of much use to governments if it does not live up to many of these same principles. In fact, some of the best services out there live up to the majority of these exact principles, simply having different opinions on what is allowed in order to participate in that particular society. This is a vital point to understand when it comes to digital identity. In order to participate in society, rules set out by the government must be followed. Local organisations must also abide by these rules. An identity offering setting out principles in advance of engaging with the government feels a bit like putting the horse before the cart or the tail wagging the dog. It’s good to have principles, but we must respect local laws and regulations, which, at the end of the day, dictate what principles can and will be followed.

Defining Ideas

We should take a step back for a moment. “Sovereignty” can simply be defined as supreme power or authority. Defining “identity” in a relatively pure sense, we can say it’s a set of attributes that together differentiate one entity from any other. In terms of citizens in many countries, this can simply be covered by a single attribute, e.g., a national ID number. Keeping these two ideas in mind, I don’t think SSI is really even about having authority over your identity, there is nothing to control - it’s a unique identifier attributed to an individual. Even looking to what is involved in acting on behalf of an identity, it’s not so much about having authority as it is simply proving that we are the one it refers to.

This is often achieved with ID cards or passports that we have in our possession with a photo to prove that we are the person this card belongs to, and therefore the person that ID number refers to. In digital identity terms, PKI takes the place of ID cards and offers public and private key pairs. The public key is “tied” to an identity, e.g. a national ID number and name, and publicly available. The public key’s corresponding private key is held by the person that identity refers to. Our identity remains that unique identifier, the national ID number, but the private key or ID card is a credential we use to act on that identity’s behalf. I have complete control over how these credentials are used, or in eIDAS terms, the identity credentials are under my sole control, as they uniquely refer to me and are physically in my possession.

All of this is to say, we have our identity and the tools to use it. At this point, there’s little, if any, concern with sovereignty or the data relating to that identity or its attributes. SSI appears much more related to data - who has control of it, how it is verified, secured, kept private, and how it can be shared, etc. This, in my opinion, is a separate topic with separate rules and supporting technologies, and we shouldn’t get the two confused or wrapped up together. An individual’s identity is only the core data that is needed to make sure that the person is who they claim to be, not all the data that can be attributed to that individual.

A Structure for Trust

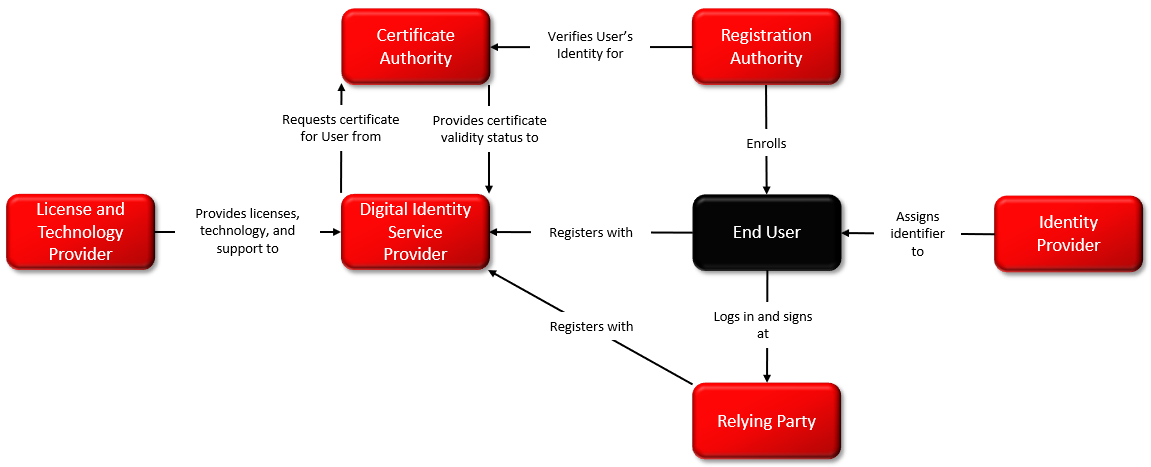

One can say that PKI doesn’t fit the “sovereign” model, because we must rely on certain players to establish our identities in a trusted way, like in the below diagram. With SSI, there is talk of decentralised identifiers (DIDs) and use of distributed ledgers to create trust. No matter what technology we tout, in order to participate in society, e.g., to get a driver’s license, open a bank account, apply for insurance, get a phone number, or apply for healthcare benefits, a trusted entity must vouch for us. With PKI, that’s the Certificate Authority - a trust service provider whose specific value is the ability for us to trust it. Blockchain or distributed ledgers might be able to maintain trust, but they do not establish it. SSI sounds appropriate in services that don’t need to know my true identity like Facebook, Google, Spotify, or Twitter, but it doesn’t fit for government or valuable societal services.

I’ve seen SSI models that explain, “A self-sovereign identity is an identity you own”. A misleading intro, as you don’t own an identity. It goes on to clarify and make a comparison between physical identity documents like passports, ID cards, driver’s licenses, etc., and the issues SSI can solve, such as the potential for theft, loss, giving away more detail than necessary, and then bureaucratic issues like lengthy and expensive application processes. All valid issues related to these kinds of documents and not being denied, and we won’t be putting a tax on sheep either.

The next comparison is with “digital identities”, but again, it’s those digital identities related to private sector offerings from companies like Facebook and Google. These two methods of identification; physical, government-issued IDs and social media log-in services, are not comparable, as they are used in very different circumstances. The digital equivalent to trusted identity documents is private keys that form part of a key pair provided to an individual once their identity has been verified by a government approved registration authority. There are different methods of registering for PKI credentials, many being comparable to physical ID document applications, which can fall foul of the same lengthy, expensive registration processes. New biometric, remote onboarding solutions are becoming a viable option though, leading to a few minutes to register, remotely, and often for free.

We Can’t Operate Without Trust

Trust is a central concept in digital identity, which is sometimes conspicuously missing from SSI principles, maybe replaced with the idea of things being “verified”. When we participate in society, specifically around high value or sensitive products and services, there must be anchors of trust somewhere in the transaction, especially when it comes to the identities of those involved. I can’t go into a bank and open an account without proof of my identity, I must show a passport or ID card, both issued by trusted government agencies. That bank can trust who I say I am, because the government has established this identity for me and provided a credential with which I can prove my identity to others. SSI is often about creating untraceable identities, even multiple identities for a single individual. This attitude is not acceptable when it comes to government-run societies, since it opens the door to fraud. Fraud is already an issue due to holes in legal and procedural frameworks that have enabled people to create multiple identities. These are then used to commit crime or take advantage of the state. This is what PKI-based digital identity is currently solving - not only to reduce multiple identity fraud, but to reduce the ability of others to claim they are someone else.

SSI and traditional PKI offerings essentially follow the same principles, looking to put the end-user in control of their identity and act on behalf of it in a way that no one else can. PKI has been offering this for decades. Again, both SSI and PKI leave privacy up to how data is exchanged, but where they differ is in how PKI centres on trust around who the individual is, while SSI centres on privacy and how data is exchanged - in my opinion, a separate topic to digital identity. So, the topic I will focus on in the next post is just that, data exchange.

Written by Maximiliaan van de Poll

Digital Identity Product Manager