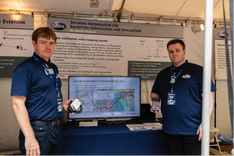

Cybernetica researchers at the Pentagon Demo Day. Dan holds the prototype tracker and Raul-Martin Rebane has the prototype smartphone app (Photo by DARPA).

Have you ever had to prove your whereabouts and felt that you are sharing too much? Let’s take a look how it’s possible to share just enough information about locations or mobility while still preserving privacy.

Location-based vehicle taxation is a recurring idea

Estonia has joined the list of countries where location-based vehicle taxation has been under discussion. One idea under consideration is taxing city drivers differently from their rural counterparts. One idea considered was GPS tracking to figure out whether a car is driven in the city or in the countryside. This proposal received criticism, for the enforcement would rely on tracking all drivers at all times. Such widespread location surveillance may not be a proportional measure to achieve its application – tax collection.

So, our scientists set out to see if we can do better. We picked a specific task inspired by the subsidy terms for electric vehicles from 2019. According to these terms, in order to qualify for up to 5000€ support for the purchase of a fully electric vehicle, you had to commit to driving 80 000 kilometres in four years and 80% of that within Estonia.

The regulation offered full GPS tracking as an option – but that collects way more data than are needed for ensuring compliance with these terms. The terms of the regulation do not ask, where exactly the person has been. This is a problem that can be solved with secure computing, more specifically, with zero-knowledge proofs (but more on that later).

We still need a source of location data, so a tracker of some sorts is needed. Our researchers made a prototype tracker device that fits in the car like the ones used to track trucks, service vehicles or certain insured vehicles. But that is where the similarities end. Here's how the system works:

- The GPS tracker in the car does not upload data automatically, it only stores the data (no automated transfer of personal information so the driver gains better confidentiality).

- At regular intervals (e.g., every three months), the user loads the trip data from the vehicle to a smartphone app. The app processes the data, calculates the information relevant to the subsidy terms and presents it for user review (driver gains transparency).

- The user decides to submit the proof. The app puts together a zero-knowledge proof stating that the data from the tracker covered a certain mileage in the defined territory and sends it to the service provider (user gains intervenability).

- The service provider receives the proof will receive and validate the zero-knowledge proof, learning the aggregates, but not the GPS trail (user gains even better confidentiality).

![]()

What technical innovation was needed to achieve this?

Zero-knowledge proof technology ensures that the personally identifiable GPS data never has to move from the end user’s premises (whether vehicle or smartphone) to the subsidy provider or third-party tracking service provider (the verifiers).

The verifiers provide the “rules” of the proof and then, the guarantees of zero-knowledge proof technology ensure the rest. Specifically, if the service provider side of the system accepts the cryptographic proof, then the verifier can be certain that the personal data (GPS trail) held by the vehicle user corresponds to the proven values (trip length and percentage in a territory).

Thus, the privacy enhancing technology avoids the day-to-day movements of an individual being processed by additional parties.

How modern science allows for privacy and innovation simultaneously

Cryptography started as a kind of art and morphed into science-based technology that's been guarding secrets through the ages. But it's not just about hiding messages anymore. Take zero-knowledge proofs, for instance. They let you prove you've solved a problem without laying out all the answers. For example, a computer can prove to another that it's cracked a sudoku puzzle without exposing all the digits.

In a larger perspective, you'll see that every task handed to a computer is like a puzzle that some official or specialist needs to solve based on the data received (for instance, to issue a permit or certificate). With zero-knowledge proofs, decision-makers can be certain they’ve got the right data for a positive decision without requiring you to disclose trade secrets or your personal data.

Cybernetica’s researchers have been building complex apps based on zero-knowledge proofs since 2020, under the US DARPA SIEVE research program and has built the ZK-SecreC toolkit. For example, apps for proving that a military recruit is in good health without transmitting their entire health record, or tracking that an organisation's donations are coming from legitimate sources.

The prototype Cybernetica built in the SIEVE program worked well and DARPA invited our team to present it at the Pentagon Demo Day in November 2023. We took our prototype for a trip from Arlington County (where both DARPA and Pentagon are found) to the Capitol in Washington, D.C. and then proved that we drove at least 3 miles in Arlington and less in D.C.

Dan and Raul-Martin collecting data for the privacy-preserving vehicle location prototype before the Pentagon Demo Day. (Photo by Dan)

Science based on the needs of today’s society

Of course, the technology needs optimisations and much more testing before large-scale deployment, but the potential is clear.

Looking ahead, zero-knowledge tech could shake things up in other domains, too. For example, with next generation ID-cards or digital identity wallets, you could prove to a sales assistant that you’re of appropriate age to purchase restricted products without them knowing your date of birth.

This is no coincidence that DARPA, funding the American defence research, is interested in zero-knowledge proofs. Cybernetica has been a part of DARPA’s research programmes since 2011. But why are defence researchers interested in privacy? This was explored in a research program named after a former justice of the Supreme Court Louis Brandeis. The thesis of the program was – if organisations and people can trust each other in the digital realm, the society can flourish.

Cryptography in defence is more relevant than ever before. For example, a tailored solution allows for countries to share information with their allies about their machines’ preliminary locations or where they are planning to move. Or even, to prove their server has not been hit by a cyberattack.

But whether it's playing nice in civilian life or flexing its muscles in defence, the golden rule is to expose just enough data and keep the rest away from the unauthorised eye. Because at the end of the day, it's all about putting people first.