The previous post focused on identity as a single topic, pulling it away from the data exchange component where it has recently become muddled up. In terms of identity, self-sovereign identity (SSI) and traditional public key infrastructure (PKI) based offerings are, for the most part, on the same page. They put control in the hands of the user, mostly differing around trust, its levels, and where it comes from. For this post, the focus is on data exchange, where both SSI and PKI put much of the responsibility for privacy.

How is Data Stored in SSI Model?

The data side of SSI mainly comes down to who stores it, how it is stored and shared, and who shares it. With SSI, the idea appears to be that the end-user must store their data - maybe on a phone or in a cloud storage service. But we can’t forget, the issuer must also store the data created by them, so we start with a situation where data is now stored in two places. This leads to the attack surface being twice as large as it needs to be. But if the end-user must store their data, the only feasible way to store it will be all in a single location; a goldmine for identity thieves. We’re now forcing the situation where all data on an individual must centralise to their phone, while it remains broken into many parts across the issuers’ databases, far less useful to an attacker. We then begin sharing portions of that data with third parties, leading to a situation where the data is now in three locations, the weakest of which is still most definitely the end-user’s method of storage, where all the data on them is accumulated. Unfortunately, the average end-user is not in a position to act in a manner necessary to protect their own data from seasoned malicious actors who steal data and identities for a career. The idea of privacy and control is certainly a positive one, but we must be careful not to sacrifice security when it comes to valuable and sensitive data, like that we use to operate in society.

Data Exchange in SSI

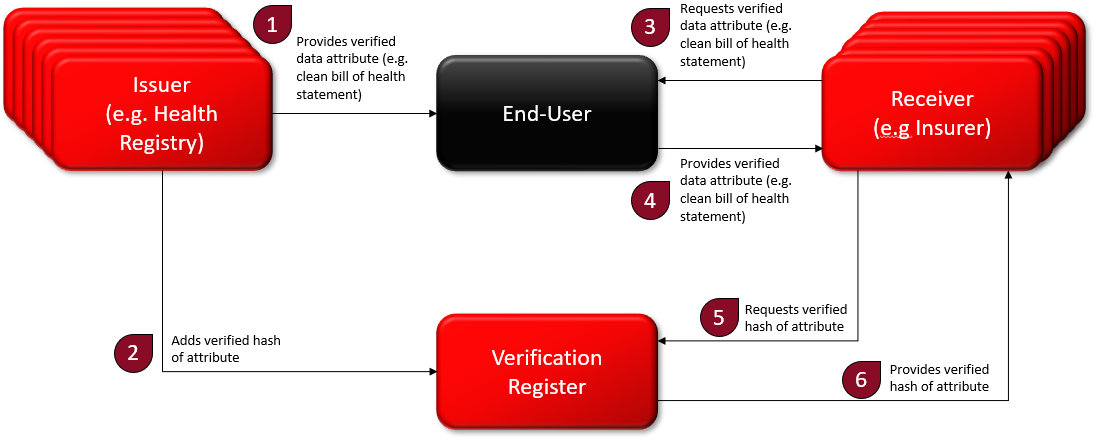

If we do consider SSI in a real-world society, we must look to sharing of data. The idea here is that the end-user can share their data without relying on the issuer of that data beyond the initial issuance. In the example below, the individual wants to share the attribute that they have a clean bill of health with their insurance provider. It need only be a “yes” or “no” response, but it must come from a trusted source, most likely a health registry or maybe the specific doctor or hospital that carried out the assessment. Once the end-user receives the data from the issuer, they can then share it when they like and with whom they like with no further interaction from the issuer. Privacy . In order for the receiver to be able to trust this data attribute, the issuer must “sign” it in a way that the receiver knows who issued the data and that it has not been altered. So, this “signature” is sent to a register of some kind, which the receiver can easily check.

Relatively straightforward, though, we are not including how anyone knows who the other is in a trusted manner, and the verification register is a new form of infrastructure that must be implemented, integrated, and managed by a trusted entity. Maybe this entity uses a blockchain. In that case, we need a (costly) managed blockchain. Still, the biggest issue relates to storage of data, nothing else is new. The verification register is effectively an OCSP (Online Certificate Status Protocol) which lets people know whether a digital signature was valid at the time of signing. Today, sharing verified documents is simply done by digitally signing a container with that document inside. Any modification of the document in transit can easily be checked, as it will affect the hash of the data that has been signed. All of this can be achieved with traditional PKI-based digital identity that has been running for decades, using trust service providers (TSPs), and a secure data exchange layer like that present in Estonia, Finland, Ukraine, Namibia, Greenland, Benin, etc.

Data Exchange with PKI

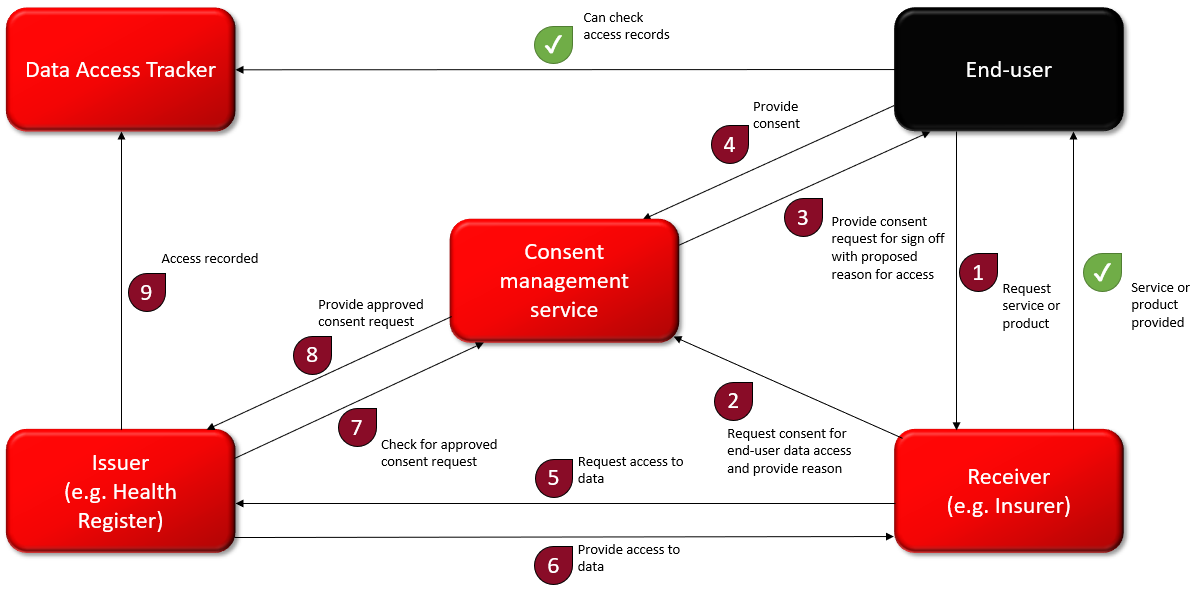

From a high level, trusted and secure data exchange can look like the below flow chart. Rather than the end-user storing all their data, they provide consent to third parties to access that data from the source. Immediately, we remove a major weak point, while keeping the most sensitive data types split between issuers by using the once only rule among government agencies, where they cannot request data available via any other government agency.

The data issuers can be public or private organisations integrated with the data exchange platform. The key is that they are the sources of the data they possess, and in that, the data they share is the most up-to-date and is verified simply by the fact that it comes from the source. Attacking any one of these data sources and creating a breach will lead to only a leakage of specific types of data they possess. This is not enough to steal an entire identity, and certainly of little benefit if PKI-based digital identity is used.

Receivers have agreements, peer-to-peer, with the data sources they require interaction with, and with permission, can access relevant data related to their citizens or customers in real time, efficiently, and securely. This way, no data travels over the open internet and data access is tracked and made available to the end-user it is relevant to, creating transparency and trust.

Privacy vs Security

It can’t be denied that we sacrifice some privacy and authority with this model, as we rely on the issuer each time we want to offer access to our data, and they in turn are aware of who is accessing it. But this model doesn’t force this approach, and when the end-user might prefer the issuer not learning who the data is being shared with, they can simply access the data themselves, receiving a digitally signed attribute with which they can share with whomever they please, privacy intact. We actually align with SSI operating that way, sacrificing some convenience and security, both in having the end-user now have to store that data, but also share it over the open web. What is worth noting about this model is that it is not new. It is how the X-Road in Estonia functions, and how it has been effectively functioning for about twenty years. It is how the X-Road and Cybernetica’s Unified Exchange Platform (the product version of the X-Road) are functioning in many countries around the world today. It is trusted because the issuers and receivers know who each other are and have direct agreements between themselves. It’s trusted because data access tracking provides transparency, and consent management can provide end-user control.

What we achieve here is a model that doesn’t negatively impact equity and inclusion, but embodies it, a model with proven interoperability, not only locally, but internationally. This is shown with the example of Estonia and Finland enabling cross-border data exchange and identity recognition. We achieve decentralisation via peer-to-peer data exchange, with data attribute types split across issuers. There is no requirement to centralise individuals’ entire sets of identity attributes in a single, insecure place like their smartphone. We achieve control, usability, accessibility, genuine and realistic security, verifiability, authenticity, transparency, and convenience. All this by utilising tried and tested technologies and processes like secure data exchange and PKI-based digital identity.

Different Types of Identity Approaches Fit for Different Purposes

Much of the point I’m looking to make here is that SSI is not presenting us with something new, rather presenting us with something not very appropriate for government-run societies. It’s presenting us with the requirement for new technologies and processes that are relatively untried and untested, aimed at replacing social media-based log-in services related to unverified and untrusted internet identities.

Estonia is an example that gains a lot of attention due to the fact it has had digital government services running for 20 years, and the country has not stood still in terms of innovation. The lessons Estonia has learnt are there for the taking, with local companies offering to share the technologies and ways of working that make Estonia what it is, and customise them in a way that fits with other governments. It is well understood that no two governments work the same, and so what Estonia has achieved is not shared with a set of preconceived principles that may or may not align with a particular government’s culture and legal landscape. Instead, these are offered in a customisable fashion with analysis, consultations, and advice on how to integrate such services into a particular government’s ways of working the best way possible.

At its core, SSI is pushing positive ideas and principles like end-user control, interoperability, and data privacy. This is a good thing, but in the SSI package, it just isn’t appropriate for governments. What it does seem appropriate for is interacting online with businesses and services that do not need to know who we are. It’s good to remove the risk of correlation, the risk of being tracked around the web so that we can be monetised and sold to. It’s good for those times we’d like to act privately. However, when it comes to banking, an industry that must work in line with AML and KYC regulations, when it comes to limiting fraud, e.g., in welfare, insurance, tax, or healthcare, our true identity is something with which there must be no doubt. I’m not saying PKI is perfect. I’m not saying what Estonia has is flawless, but in terms of fraud, identity theft, ease of government interaction, I know no better. We have an excellent foundation for governments - well-regulated, tried and tested – let’s build on it.

Written by Maximiliaan van de Poll

Digital Identity Product Manager